|

Eric Ortiz / [email protected]

Wedge resident & volunteer LHENA board member

Grassroots democracy is not easy. The work is rooted in community and empowers people to take leadership into their own communities. It requires passion, commitment and courage. And sometimes, it can get messy. That's what happens when there are big problems to solve.

Here in Minneapolis, we have some pressing issues. Crime is up. Gun violence is up. Public morale is down. Citizens are concerned. As neighborhood leaders, we do not want to wait for something to turn the tide. We want to push momentum forward in productive ways that help us identify the priorities and figure out ways we can all work together to address them. On Oct. 21, the Lowry Hill East Neighborhood Neighborhood Association (LHENA) hosted a public safety forum with boots-on-the-ground community leaders in Minneapolis. The conversation was on Zoom and Facebook, and participants included:

Korey Dean, The Man Up Club Lisa Clemons, A Mother’s Love Initiative Raeisha Williams, Guns Down Love Up Charles Caine, Brothers Empowered Chief Medaria Arradondo, Minneapolis Police Department (MPD) Inspector Amelia Huffman, Fifth Precinct, MPD "The main thing that we have been addressing and can address as an organization is mentorship. Bring back that village mentality."

Korey Dean is the founder and executive director of The Man Up Club, a mentor-leadership organization that launched in 2012 and mentors young Black males between the ages of 12 and 24. The nonoprofit organization teaches life skills, social skills and academic discipline and has three goals: "to get our young black males to graduate from high school, to keep them out of the prison pipeline, and then to either go on to college or develop a trade or career after high school."

Dean was joined by some young men from the Man Up Club who are focused on career development, education and jobs. One of them spoke about what life is like right now being a young Black male in the Twin Cities. "It's pretty hard," he said. "Trying to find a job kind of gets hard." Another young man said, "Honestly, life in the inner city right now is pretty hard. As we all know, the whole topic of this meeting is crime, and I've lost a lot of people to gun violence. To process that and realize that you've lost a friend, or a family member, or whatever the case is, it's a situation that could have been prevented if we just took certain policies serious. It's hard to overcome, but in the end, if we all work together, and come up with a solution, I am pretty sure it won't last forever." The people closest to the problems often have the best ideas for solutions. But too often the voices of those most impacted by crime and gun violence are not heard. We need to start listening to the community and stop making decisions without them. This is how we can begin to change the narrative.

Charles Caine is the founder of Brothers Empowered, a self-funded community mentorship organization based in Minneapolis that started in 2014. He explained how he was able to make an immediate impact in the community.

"One of the reasons why we were able to make an instant impact is having men who were rooted, grounded in the community, stable-minded men, sound-minded men, pillars in the community," Caine said. "So our goal was to create pillars within the community. We saw that every successful community had men who were pillars in the community that were giving back or had commitments in that community, whether it was business, whether it was with family, whether it was religion, there were pillars in the community. We were suffering because we didn't have enough men who were sound-minded in the community. So that was the mission and motive of Brothers Empowered. Create sound-minded Black leaders in the community." Caine gave his thoughts on the safety situation. "There are so many factors. It's an economic issue, job, housing, drug and chemical dependency issue. We have a large rate of homeless teens in this country. The educational and economic gap between Black and white is one of the worst in the nation. The main thing that we have been addressing and can address as an organization is mentorship. Bring back that village mentality. That uncle mentality. I'm a product of a mentor. So I know that it works personally. When I was a young man growing up in North Minneapolis, there was a guy that I'm sure you know, V.J. Smith, before he even started Mad Dads, he took me under his wing. He would take me lunch, show me colleges, spend time with me. That meant a lot. That helped to impact my life as a young man." "When you operate in silos, all the other violence gets to skate through, all the young people that need your help, they slip through the cracks because we're not working together in a unified effort."

Lisa Clemons is a longtime Minneapolis community activist and organizer and former MPD officer. She started A Mother's Love in 2014 to bring back the village and has a team composed of women and men that reflects the communities they serve.

"It was really hard to get started because I don't think people are used to having a woman with boots on the ground," Clemons said. "It was hard to get the women involved. But I need the community to know that the women needed a voice, not to just speak on their daughters, but to speak on their sons. Because 70 percent of households, many in North Minneapolis, are headed by a single Black mom. So we don't just mother daughters. We mother sons also. That's no dig on my African-American brothers, because they are in this fight with us." Clemons deals with a lot of the violence in the community, and that's what she talks most about, the violence in the community. "We try to mentor also," added Clemons. "The problem is the division of the mentorship. We all operate in silos. When you operate in silos, all the other violence gets to skate through, all the young people that need your help, they slip through the cracks because we're not working together in a unified effort." Clemons is all about solutions to the violence, and that's where we all have to be focused on now. Getting all of the community mentorship groups to work together will be key. "(Chief Arradondo) came up to me in humanity, in kindness. He spoke to me in a respectful manner, said, 'Whatever you need, let me know. I'm here for you.' And that's the difference between community policing and white supremacists who get on the police force and are racist and already have racist views and interactions with Black people."

Raeisha Williams is an activist with Guns Down Love Up, which was started in 2019, and like all of the other organizations on the panel, she is doing the work on the ground.

"There are so many reasons why gun violence is so prominent, not just one," she said. "So it's being able to have multiple groups. Many different organizations. Many different neighborhood associations taking responsibility for it and stepping up and trying to create solutions." She has experienced the violence firsthand and lived the journey with community harm. Her brother, Tyrone Williams, a community activist and racial justice activist, was murdered in front of her mother's house. She and her family gained a better understanding of what losing a loved one means. Guns Down Love Up focuses on three areas: prevention, intervention and restorative justice. "We are a small group, all volunteers, very underfunded. We can't do everything," said Williams. "That's why we like partnering with other organizations like Lisa Clemons, Brothers Empowered, and the Man Up Club. Chief Rondo even attended a few events. We're all collectively doing the work. Even if we work in different areas. The ultimate goal is to create solutions for gun violence." "One group, one police department cannot do it all. There is not one solution to all of the issues and problems that created gun violence."

Korey Dean from the Man Up Club raised another important point. Besides the need to bring back the village approach and get outside silos, there is a third layer to the problem of gun violence — money.

"I think one of the greatest issues that we face when it comes to gun violence, and even programming, is funding," Dean said. "All of these organizations that are on this call right now are underfunded. That's a big issue. In order to make long-term, sustainable change, you have to have long-term sustainable funding. That people can see the value. Wherever you put your dollars at, I think that's where you put your value at. And if there are no dollars in the inner city, then there is no value in the inner city. "When you talk to a lot of these organizations, the issues are mounting issues as far as violence, but the resources are scarce. Now let me quantify that. The resources that are scarce in the community, they're not scarce in the city. And they're not scarce in the state. But the funneling process to get those dollars to grassroots organizations that need them on the ground that's something that we have to systematically fix so that those funds can flow down because the work that we are doing, though it may be illuminated, it needs to be effective and impactful. In order to make it impactful, we have to start getting into the six-figure numbers where we can provide them adequate resources outside of school and outside of their homes." The Minneapolis Police Department has a 150-year history in Minneapolis. The current backlash against the MPD (and against policing across the United States) did not start with the George Floyd killing on Memorial Day. The MPD (and policing in the U.S.) has earned that over a long history. Minneapolis Police Chief Medaria Arradondo is doing his best to lead the MPD in these unstable times. We invited the police to be part of this panel because we believe they should be part of this conversation, and we want to discuss ways we all can work together toward public safety in the community. "Every young person got to see themselves 20 years from now."

Chief Arradondo, a fifth-generation Minnesotan, joined the MPD in 1989 as a patrol officer. In 2017, he became the 53rd chief of the Minneapolis Police Department and the city's first African-American police chief (he also is Latino of Colombian descent). Chief Arradondo has great respect for the work grassroots community organizations do. He knew and worked with the other speakers on this panel before he became chief and has collaborated with their organizations.

"This work is too great and the time is too short. One organization cannot do it alone," said Chief Arradondo. "The police department will never be able to solve many of the society issues that we are plagued with at times. Community safety, I believe, is a part of an ecosystem. Policing is just one piece of that. But it really relies upon all of that." The chief echoed the need for mentorship. "We need more mentorship. Absolutely. We are going to need everybody. It's an all hands on deck to really try to address this trauma that is impacting our communities. I am committed to continuing to support, be an ally, with the important work all of the leaders on the call are doing and will continue to do that." A community member, Bill Rodriguez had a question for the chief about staffing levels. Rodriguez runs a Facebook group called Operation Safety Now and has proposed a 60-day plan to address the spikes in crime and violence. The chief expressed concerns about staffing levels. "We are at a critical juncture right now with public safety," said the chief. "Yes, we have mutual aid agreements, and I will have to continue to rely upon our mutual aid partners, whether that's Hennepin County Sheriff’s Office, Metro Transit Police Department, U of M, and others. … What part of the city am I focused on? All four corners. And I will move heaven and earth to make sure all of our communities are safe. But I am going to need resources for that. "[W]e need good public safety. I don't want police officers out there harming our community. We will not break the law to enforce the law. But I need resources. And again it's a village mentality. I need the work of Guns Down Love Up. I need the work of Mr. Dean's group. I need the work of Mr. Caine to do what he's doing. And Miss Raeisha. We all need to work together in this ecosystem. Resources are depleted and diminishing rapidly. … I will utilize and take as many resources as I can to keep our city safe. I will continue to operate in the narrative that is both and. We need more public safety resources. At the same time, I want to support the work [of community organizations.] Those groups need to be funded as well."

The chief was asked about the Black community's relationship with the police and the harm that has been caused and whether their lives matter. "Yes, their lives absolutely matter," said Chief Arradondo. "There is a reason why I decided 31 years to work back in the community that nurtured me and gave me an opportunity. I'm from Minneapolis. I was born and raised in North Minneapolis when we called it the projects. But grew up as a child in South Minneapolis. We have to, we have to see each other as necessary. These young kings that are sitting around Mr. Dean, their lives do matter. And the sanctity of life matters. And anytime a life is taken, particularly when a child is taken from our community, that impacts all of us. I am tired of going to funerals. I need to make sure that we are doing everything we can so that our men and women just truly understand their importance. What is occurring today cannot be their normal for tomorrow. That pain is real, and I hear from it.

"So one of the things I do personally is I make sure I am in conversations with these young kings that Mr. Dean has surrounded by him. I also go out to our prisons. I know there is trauma that affects people along the way and journeys. I am not trying to increase our prison system here in Minnesota. My job is not to keep Sheriff Hutchinson's jail full. If there is any way possible to give our young men an opportunity and restore hope in their lives, I want to make sure I can do that the best way I can. At the same time, we have to hold our communities accountability for violence and harm. I want to make sure our officers truly can see and interact and engage with our young men and women. Their lives absolutely do matter. So I will continue to work toward that each and every day. I have an obligation to them. So I will continue to be dedicated to that." "The way violence is distributed across the city is very unequal."

Raeisha Williams recounted a story of when she had her first personal encounter with Chief Arradondo. It was during the Jamar Clark protests when they were occupying the Fourth Precinct in 2015. "He came up to me not knowing me. He came up to me in humanity, in kindness. He spoke to me in a respectful manner, said, 'Whatever you need, let me know. I'm here for you.' And that's the difference between community policing and white supremacists who get on the police force and are racist and already have racist views and interactions with Black people."

Williams posed a key question about the police: "How do we clean house? I'm glad that all of the officers who have stepped down, have stepped down. Sometimes, it has to be really, really uncomfortable before it gets better. I'm happy that Rondo is in the position that he is in. We as activists and community members asked for Rondo. We haven't had a Black police officer who was a police chief ever, who was from the Twin Cities, born and raised. That goes to the pipeline, when you talk about youth. North Minneapolis, North High, Henry, Washburn, all of our community schools should have a pipeline to policing. So that if our young people in our communities want to be police officers, like Lisa Clemons and Rondo, they have an opportunity to do that. Because when you police your own community, you treat them with more dignity, respect and humanity. Because you see your mom, your aunt, your cousin in them. "Our police force is less than 3 percent of local police officers who are residents. Can you imagine 90 percent of Blaine's officers being Black men from North Minneapolis, going in to get those jobs, get those pensions, and then not even spend the money in Blaine. Could you imagine that? And could you imagine all of these Black officers murdering white Blaine residents? And they don't live there, they're not from the community. If it happened once, there would be a total different outcry. And this goes to systemic racism and how it's embedded in the policing. So it's not that all police officers are bad. "And trust me, I hold all officers accountable as an activist who's always been on the front line calling them out. I've called Rondo out. But I also believe that if I have, for instance, when my brother was murdered, who can I call? Who can I call? If I don't have the police to call, there is no other department, there is no other way to get that justice. I need police officers to show up respectful, treat me with humanity and dignity, and stop killing us, and stop profiling us. But that's a bigger issue. It's getting rid of white supremacy in the police force. Cleaning house and bringing in officers. It's not going to be the National Guard. White supremacy is all through there. It's about bringing in real people who want to do real policing and community work." Lisa Clemons made a keen observation, "The real sign of a true leader is when you piss off other cops. So that's what Chief Arradondo does by making reforms and changes. He pisses off other cops. That's a good thing. What he does not have is the support of a city council. You can't ask for somebody to make reforms and then not support them in the efforts to make reforms. I am very proud of everything Raeisha said on here. What I love about her is that no matter how she feels about cops, she supports this chief. We all stand behind this chief. We all expect the changes to come that involve us in those changes." Clemons also defended Deputy Chief Art Knight, who was demoted to lieutenant by Chief Aradondo for telling the Oct. 18 edition of Minneapolis Star Tribune, "If we keep employing the same tactics, you're going to keep getting the same white boys." Knight was referring to the way the MPD recruits, trains and promotes people of color and women on the force. The punishment, Clemons believes, was much too harsh. "Regardless of what anybody feels about him using the word 'white boy' or 'white officer' or 'white cop,' we all knew what his message was. And that is, if you are serious about diversity in the Minneapolis Police Department, there are routes that you need to take to get that diversity into the Minneapolis Police Department. So I stand behind him. … We all knew exactly what he meant. The message got lost in one word, and that's 'boy.'" "Housing impacts everything we do in terms of true community safety."

Clemons had more words that need to be heard.

"We keep ignoring that Black women and Black daughters are being killed out in these streets, too. That a lot of the fights that happen between our Black men involves our Black women and our Black daughters and Black mothers," said Clemons. "Every time we have this conversation, our whole focus is one-sided. And I'll tell you what I say and most of you have heard it. You save the mother, you save the child. Seventy percent of mothers are single heads of households. You save the father, because you have to work on them both at the same time, not separately. You save the father, you save the family. Once you start saving whole families, you save communities. Now until we remember that, and when we talk about funding I'm telling you what's real, this work is not easy. "Change is not going to come with you nickel and diming everybody. And then taking money from the police department and saying we're going to defund you and put this money into this and I want somebody to raise their hand on here and tell me where that defunded money from the police department went in helping us make change in the community. I get real tired about talking about this. I get emotional about this. I stand with this police chief on everything he trying to do. He make me mad at times. But I stand with this man on everything he do, everything he represents. I hope Chief Knight don't leave the Minneapolis Police Department. I stand with him on everything he says and everything he does. If you want change in the community, the city council members, they got to go. They are impeding the work that we all need to be doing together in a joint effort to save these lives. This is no longer in the containment zone of North Minneapolis. This is city-wide and moving to the suburbs." Lisa Clemons said she has not gotten any city funding because she did not want to wear the orange shirt of the violence interruptors in Minneapolis. They are paid employees of the city's Office of Violence Prevention, and the violence interrupters program launched in September 2020 as part of the MinneapolUS Strategic Outreach Initiative. Clemons said she spent six years building her brand and did not want to build a brand for the city council for a check. Raeisha Williams also called out the city council when it comes to funding. "They're playing games. They don't want to give the money to real groups. You may not like me. You may not like the way I move. But the difference is I am creating solutions and real change in my community. We have to get over I don't like her. Or it's a political game. Because we are losing lives. We are losing our children's lives." In July 2020, the Minneapolis City Council approved moving $1.1 million from the MPD to the city's office of violence prevention. Williams questioned why the city council would create a group and give them all of the money when other groups were established and already doing positive work. When talking about funding, Williams cited that move, "I'm not offended that we didn't get funded. That's OK. And I'm not offended one group over me got funded. That's also OK. But you can't give $1.5 million toward one group and expect them to do all the work. That's what we talked about earlier. It should have been multiple groups doing multiple different solution work and activities in the community. One group, one police department cannot do it all. There is not one solution to all of the issues and problems that created gun violence. So when we talk about funding, make it equitable and get out of the politics." Charles Caine added, "We have been self-funded for six years. I'm on Broadway and Emerson right now where we fed, we gave away $25,000 meals throughout April through August throughout the whole quarantine. One of our passions is giving back. Giving back. Period. Because it becomes bigger than just yourself. As men, young and old, we have a duty in the foundation to give back." He's also not surprised about the lack of funding. "I'm not surprised we're underfunded or overlooked. Because we're a volunteer-based organization. Everybody in our program do it from their heart. We have fed over a 100,000 people in six years. We've given backpacks, bikes, done community peacekeeping. And most of this is volunteer based. This is what we do. If you want to make a change, give the money to those who are doing the work from their heart. Those who are really out here doing the work and it ain't about no money. "We don't need money in Brothers Empowered. We don't need the state, the city, the county, the grant money in Brothers Empowered to do what we do. We have been doing it six years. Self-funded. We have created businesses. Like Honor Roll Athletics. Which is part of our business management training program for the youth in our program. We're teaching them how to run and manage businesses. We have a youth advisory board that make decisions on Honor Roll Athletics. And a portion of the proceeds go back to the organization, which is rooted in the community so it goes back to the community. "We have started up different other businesses. Power to Win, essential oils. We have started other businesses. We have created a video and audio production company. We're looking into expanding into other businesses, which is connected to our business training and management program teaching the youth how to become entrepreneurs. Because all these dudes that are out here on these streets, with all this time on their hands, being an entrepreneur means you create and have control of your time, you do what you want to do. And these young people, it's all about control of their own time, doing what they want to do. Why put that energy into being on the corner, where you're making the salary of a McDonald's employee, $30,000, $20,000 a year. That ain't no money, if you're out here a corner boy. You're gonna be the one that's gonna take the body and gonna go to jail and gonna be making 15 cents an hour, after taxes 8 cents. "So we're teaching them how to run and manage a business and create their own lane, so that they can utilize those entrepreneurial skills into something productive. If I can get them busy into doing something they enjoy doing, whether it's fashion, music, video, whether it's culinary, whether it's automotive, whatever, then that takes their time away from these knuckleheads. Because every young person got to see themselves 20 years from now. And the problem is, these youngsters don't see themselves two years from now. They want to go visit their homies in jail. They want to go with their homeboy and brother that was shot last year or last month. That's the problem. They have developed a combatant mentality, a do-or-die mentality. And they're too young to have that mentality. "I'm not surprised that organizations that have been out here doing the work don't get funded. … The system don't really want to see no real change. They don't want to see no real change. So there is always going to be a band-aid on the sore, on the cut. … I'm not into politics like that. I don't chase the funds like that. The system don't really want us to see change in our community. But we have to do, I'm speaking to Lisa, Raeisha and everybody else that is about this, we have to make change on ourselves. And then the system will run and beg us to take their money."

Inspector Amelia Huffman of the Fifth Precinct, whom Chief Arradondo praised as a great leader, patiently waited for more than an hour on the call before she got a chance to speak.

"The situation here in the Fifth Precinct is substantially different from what folks are working with in the Fourth Precinct in North Minneapolis or in the Third Precinct on the east side of 35W," Inspector Huffman said. "When you look at the spike in violence that has happened this year and the incredible rise we have seen in shootings, it is really unevenly distributed across the city. Seven percent of the shooting victims this year have been in the Fifth Precinct, and the vast majority of the rest of the shooting victims have been in the Third Precinct and the Fourth Precinct. The way violence is distributed across the city is very unequal. "When you look at violence in the Fifth Precinct here, it is very clear that it is also unequally distributed here. Whittier, Lowry Hill East and Stevens Square are the three most crime-burdened neighborhoods in the Fifth Precinct of the 20 neighborhoods that make up Southwest Minneapolis. That includes both property crimes and violent crimes. So even though our share of violent crimes is much smaller than some of the other precincts are contending with, we have violent crime hot spots in this precinct. Pretty stably over the last 10 years, we've had three primarily violent hot spots. One is in Uptown at Lake and Hennepin and Lake and Lagoon. One is at Lake and Pillsbury and the other is at Franklin and Nicolett. "In the past, we have had beat officers working in those areas, we have had extra focused patrol resources, we've had a community response team to work on some neighborhood complaints to work with businesses, neighborhood organizations. As the chief mentioned, as the department grows smaller, and as we become much more one-dimensional, our ability to staff those kind of positions is shrinking as well. We have lost those resources. Next year, we will not be able to staff those kind of positions. We will have fewer investigators here at the precinct. We will have no beat officers here at the precinct. We also will not have a community response team. With our own precinct resources, we will not have the ability to do plainclothe investigations to follow up on neighborhood complaints about problem properties, drug activity, street-level, low-level violence, those kind of projects and work we used to do in the past will have to be shared among citywide resources. Just in a snapshot, that's what we're looking at here in the fifth precinct right now and going into next year. " We need to have an ecosystem of public safety. One of the problems is we have lost a lot of trust in one part of that ecosystem, the Minneapolis Police Department. How do we heal that lack of trust? How do we get more effective accountability? What could change the game for this year and for the next five years? The speakers shared their ideas for reforms. Lisa Clemons would like to see boots-on-the-ground organizations and police working in a strong partnership. "Getting to know each other. Our wants and unwants. Likes and dislikes. Things we agree on. People would be shocked how much we have in common. Put biases at the door. Want to have real conversations with cops and our youth with no holds barred. Real conversations in a room with just them to talk to each other. Without anybody getting angry about it. I would like to start building bridges between the police department and the community. Real bridges."

This type of relational building can lead to transformative justice. First, we have to rethink what's possible and ask: How? How do we prevent and stop violence and harm without creating more violence and harm? How do we transform a society in which harm is endemic to build a culture where violence becomes unthinkable? Small everyday acts of accountability and relationship building can lead to a cultural shift away from harm.

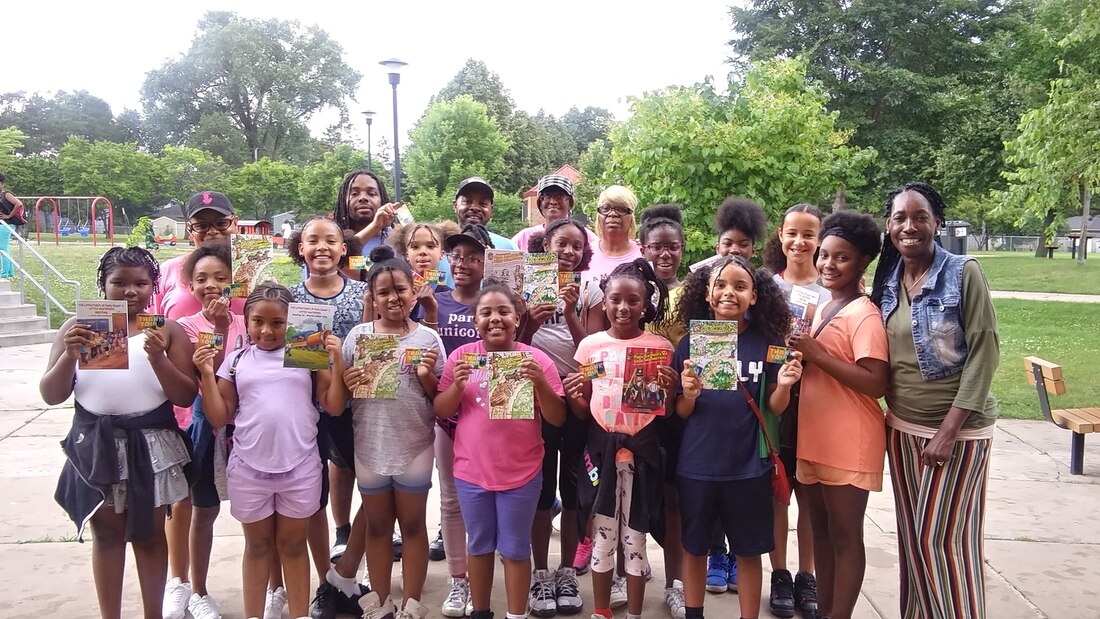

Charles Caine shared his thoughts on police. "Yes, we need to hire a lot more officers and have them be a part of the community. There should be commanding officers, lieutenants, that are from the community. That are working in that department. Because you have the heart of the community. You live there. When you live somewhere, there is more of an investment. Have more officers residing in the community where they work. Doesn't matter what color they are. If they reside in that community for 5-10 years, you are a part of that community. "I also believe those officers should be working hand-in-hand with their neighborhood associations. Those officers should be a direct liaison that are working with the neighborhood associations that deals with complaints. I believe the neighborhood association should deal with the complaints. Neighborhood associations are open to anybody. There should be more exposure of neighborhood associations to get residents and community leaders into part of neighborhood associations and crime and safety division of neighborhood associations to deal with those complaints. A lot of those officers are complained and all they do is switch them. " Caine supports Chief Arradondo and created a new tagline. "Rocking with Chief Rondo. This is something bigger than Chief Rondo. This is something that has been in existence for years upon years. He can't make an instant change. I definitely rock with him. We don't have deep a relationship, but I have researched and learned a lot about him." How do we transform accountability and give it back to the community? LHENA residents shared some ideas at a community public safety workshop at Mueller Park on Oct. 10, and Chief Rondo is open to listening to the community. "I am supportive of police oversight," he said. "We have a mechanism right now through the office police conduct review. Years before that, we had an interaction of that civilian review authority. Never a perfect system. Any sort of mechanism where we can have some community oversight is important." But one of the biggest problems we still have to address is the housing issue. "Housing impacts everything we do in terms of true community safety," Chief Arradondo said.

Community is more important than ever. People want to get more engaged in public safety in a much more deeper level than what we have been. Thanks to technology, we now have the ability to talk to each other across different parts of the city.

LHENA plans to do more forums on public safety and use these conversations to create solutions. The idea is to create a community ecosystem that connects all of the community mentorship and leadership groups doing great, positive work with boots on the ground. We want to create a mobilized community force so everyone is connected, working together instead of in silos, to increase the peace and create more opportunities and justice for all. If you are interested in collaborating with us on this initiative, please contact LHENA president Alicia Gibson at [email protected] and LHENA board member Eric Ortiz at [email protected].

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed